When Erin and I found the address we’d been given for Brouwerij De Glazen Toren, we were sure there’d been a mistake: we were standing in front of a suburban-style house with a large garage on a residential street in a little village. It turned out that the large garage was actually a very small brewery run as a retirement project by Jef Van den Steen and two friends.

We barely had a chance to say hello to Jef’s partner Dirk De Pauw, because as we arrived he was loading a case of beer into his car and leaving on a run to a nearby brewery to trade beer for yeast. Glazen Toren is too small a brewery for yeast propagation equipment, and they brew too infrequently to maintain all of the different strains they use for their various beers. Instead, they decide which local brewery’s yeast would work well with that week’s brew, and they trade beer for it.

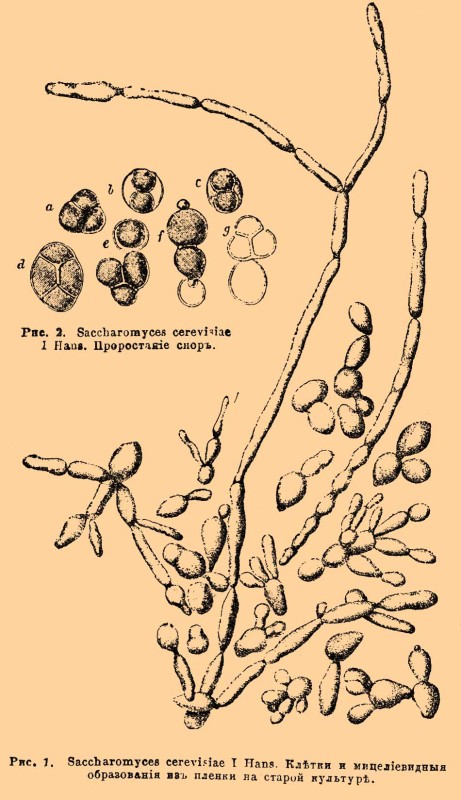

In the old days, yeast was an extremely local ingredient of beer. Beer was fermented by whatever wild yeast happened to float by on the wind, which varied with local climate and geography. In one village, beer might be fermented by whatever yeast lived on the fruit skins from a nearby orchard. A couple of kilometers down the road there could be another orchard with different fruit and a different airborne fermentation culture that produced different-tasting beer.

When brewers began to domesticate yeast by reusing slurries that had made good beer, a newly-domesticated strain of yeast would be confined to one brewery. But when the brewery down the road had a fermentation problem, the brewer might come to borrow some yeast and carry a slurry of that particular strain home with him in a bucket, making a house yeast into a village yeast. If it was an exceptionally good yeast, it might be shared again and again and become a regional yeast.

Breweries sharing yeast used to be common practice. A healthy fermentation produces much more yeast than is needed to brew the next batch of beer, so if it isn’t given away, that excess yeast would just be discarded. Some breweries are getting more tight-fisted about sharing the biological property that is responsible for so much of their beer’s unique character, but there are other ways to get yeast now.

Trading beer for yeast sounds like a nice way to operate, but nowadays most breweries get new yeast from labs run by universities and private companies. These labs maintain libraries of hundreds of strains of cryogenically frozen yeast, which they will propagate on demand for breweries.

In Vancouver, we’re lucky to be close to the American west coast, the epicentre of that country’s beer revolution. In Hood River, Oregon, Wyeast maintains and propagates world class brewing yeast and sells it to both commercial breweries and homebrewers.

It is a strain of their yeast on which Dageraad’s core beers will be based. I first came across it at Dan’s Homebrew Supplies on East Hastings. The first beer I brewed with it absolutely hooked me. It was a beautiful Belgian blonde, fruity, complex and subtle. It was beginner’s luck. It would be a year before I’d manage to brew another beer as good as the first one.

But Wyeast doesn’t create its yeast strains from nothing. They scour the world’s breweries for their yeast, capturing, cataloging and storing the brewing world’s biological treasures and making them available to brewers everywhere.

Wyeast doesn’t say which particular brewery each yeast strain comes from, but certain brewing experts have some educated guesses, and these experts and my palate agree that Dageraad Brewing’s yeast strain comes from a brewery in a tiny village in the Belgian Ardennes.